Ben Lando | February 10, 2022

When Esperance Mukeshayezu came to the U.S. in 2005, she was only fluent in French and Kinyarwanda, two of the languages common in Rwanda.

She didn’t know where she would end up if she and her baby daughter survived the walk in 1994 to neighboring countries to escape a genocide.

When she got here, Mukeshayezu didn’t know if other members of her family were still alive.

“I thought everyone was dead,” she says. “It was a very, very terrible time in my country.”

The Kalamazoo community has become a haven for new neighbors when circumstances in their home country have become too dangerous to survive.

Hundreds of people are in some stage of the process of starting a new life in Kalamazoo having escaped Taliban-controlled Afghanistan last year. Like Mukeshayezu, many will need assistance to access the various services to restart a life here – a new country with unfamiliar customs and systems – and receive help to process the often traumatic experiences.

Access isn’t as easy as making an appointment and showing up – especially without the ability to read and speak English.

“Language access is a huge barrier that keeps people from being able to communicate at work, get a job, participate in their children’s education, and participate in health care,” says Jackie Denooyer with the Kalamazoo Literacy Council. “All of those things make it a worthwhile investment so that people who live here are able to be full members of the community.”

Denooyer is a “navigator” at the Council, who helps find transportation, resources like medical care, participate in conversations with landlords, and obtain food.

Mukeshayezu is in the Literacy Council’s English as a Second Language (ESL) program, which currently provides both traditional English language skills as well as computer and other digital training to 136 students from more than 17 countries, Denooyer says.

The Kalamazoo Literacy Council started in 1974 and took over the then-independent ESL of Southwest Michigan in 2017. Its virtual and in-person classes, staff salaries, and equipment is funded by a number of government and philanthropic grants focused on both disaster relief and workforce development.

It’s in need of more volunteer ESL tutors and instructors, for which it offers training. Refugees in particular have needs that require a trained and empathetic ear. To help its teachers and members of the community recognize and handle those needs, the Literacy Council is holding a special training session on February 12, 2022.

Denooyer says it will help teachers and volunteers avoid “land mines” when working with refugees.

“There may be trauma there,” Denooyer says. And that means, “Being very, very careful in the interactions with them about the type of questions you might ask. Someone who has recently fled a war zone might not want to tell you the story of how they came to the United States.”

For example, Denooyer says it may not be a good idea to ask refugees about family members left behind, or who died in a conflict.

Mukeshayezu is quick to laugh. Neither her language skills nor experience nearly three decades ago escaping genocide is a match for her storytelling or determination.

All ESL students in the Kalamazoo Literacy Council program, including refugees, are assessed when they join and are placed in classes at their level, from beginners to those whose English skills are more advanced.

“It was very hard. I didn’t understand anything,” Mukeshayezu recalls of her arrival to Kalamazoo. “I learn because there’s no choice. This is important.”

She picked up enough of the local languages to work in both the Republic of Congo, where she lived from 1994 to 1997, and then in the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1997 to 1999. As violence in those countries and threats to refugees continued, she kept moving, on to Cameroon where she could fluently speak French.

Six years later, safe in Kalamazoo, she received help from families and staff from places like Bethany Christian Services who support refugees, providing linguistic and cultural translation for things like how to pay bills.

She took classes then as well, but stopped when she had to work two jobs.

Now, her grown children are living in the Kalamazoo area too, although the fate of their father remains unknown. Her grandchildren only speak English. Mukeshayezu now owns a house in Portage, with help from a local church, she says, and works on a team that cleans operating rooms at Bronson Methodist Hospital.

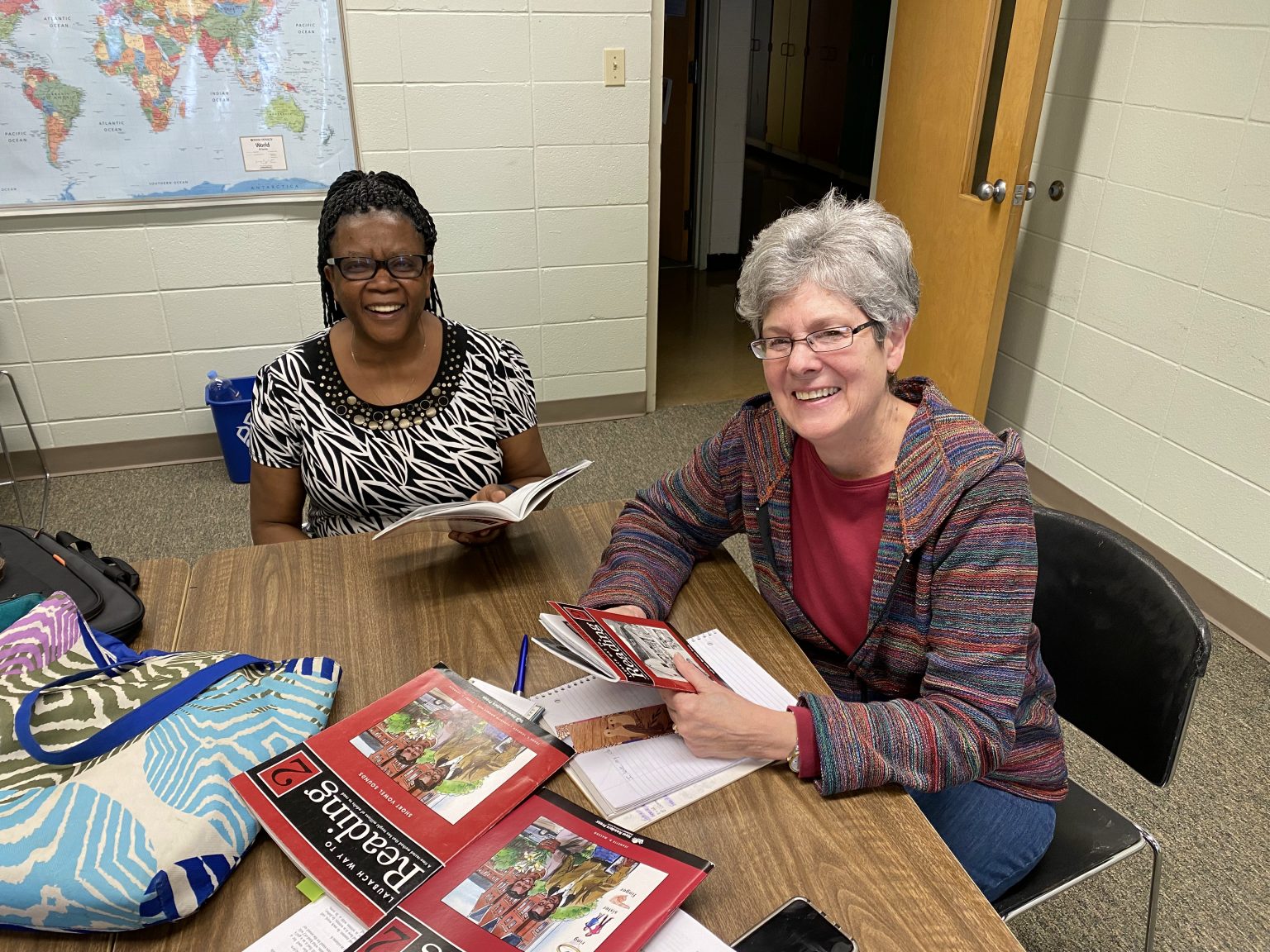

Since January 2021, she’s been meeting with Literacy Council volunteer tutor Carol Pratt, a Kellogg Company retiree who joined the program in 2015. At first, she and Mukeshayezu worked together online because of the pandemic. But now they sit together for 90 minutes, three days a week, at Prince of Peace Lutheran Church in Portage.

The sessions involve practicing new words and sentences using techniques like rhyme, among other things. The program helps her communicate at work, where some of her teammates have Spanish as their first language.

“She’s reading new words, reading new sentences, and understanding the sentences and saying them,” says Pratt. “I think education goes two ways. I’m learning and Esperance is learning.”